The Creole Family Business

From the first generations of colonial rule, Creole life in Louisiana exhibited a unique, characteristic thread: the understanding that the family operated as a business and that the business was family. Whereas Laura's family considered their French Quarter townhouses in New Orleans as home, the plantation was where they went to work and the font from which every family member's income flowed.

Laura's family came to the plantation in the spring to get the sugar crop underway and worked here until around Christmas, until the end of grinding. They traveled frequently back & forth from farm to city for 9 months but, in January, February and March, the family remained in New Orleans for the Season.

Laura's family came to the plantation in the spring to get the sugar crop underway and worked here until around Christmas, until the end of grinding. They traveled frequently back & forth from farm to city for 9 months but, in January, February and March, the family remained in New Orleans for the Season.

Everyone in the family was a member of the business, each with his or her own accountable role. Early on, l'habitation Duparc consisted of the immediate Duparc clan, with children and their spouses as officers. Apart from this nuclear family, the plantation workforce often included aunts, uncles, cousins and adopted and fostered children. As well, there lived on the place, men contracted as managers and overseers, with their families on-site, the plantation slaves accounted for 80% of the plantation residents. And, then, there remained a small group of native Indians, all of these people, inhabitants of what they attempted to have: a self-sufficient enterprise.

With each succeeding generation, Creoles, who already owned most of the valuable real estate in Louisiana, created businesses that encompassed far-reaching networks of cousins in related occupations and in politics. The Duparcs were a prime example of this, having family and commercial ties from Natchitoches in north Louisiana, on the Red River in central Louisiana, and along the Mississippi River plantation belt, and down into New Orleans.

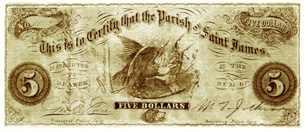

In a desperate attempt to break the strangle-hold that Creoles held on Louisiana real estate, natural resources and the sugar & cotton-based economy, the Americans enforced the alrady existing laws of forced inheritance upon all citizens. The Anglo intent was to destroy the Creole estates, carving them into ever smaller pieces and making them more available to American buyers. To thwart this Anglo intrusion, the Creoles responded by forming family partnerships and corporation-like family enterprises. Clearly, this was the case when in 1829 Nanette Prud'homme Duparc created, along with her three children, the Duparc Freres et Locoul Sugar Company.

While Creole Louisiana was defending itself from Anglo business interests, demand for Louisiana sugar and cotton created quick and vast fortunes for those plantations that were capable of meeting the market's demand. By the 1840s, this plantation had seen 20 straight years of healthy profits. The Civil War and subsequent economic depressions caused the demise of these agricultural family businesses, but vestiges of this long Creole tradition survive along Louisiana's Great River Road to this day.