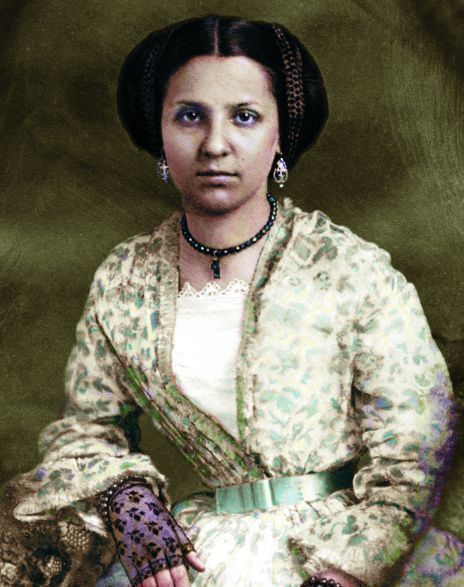

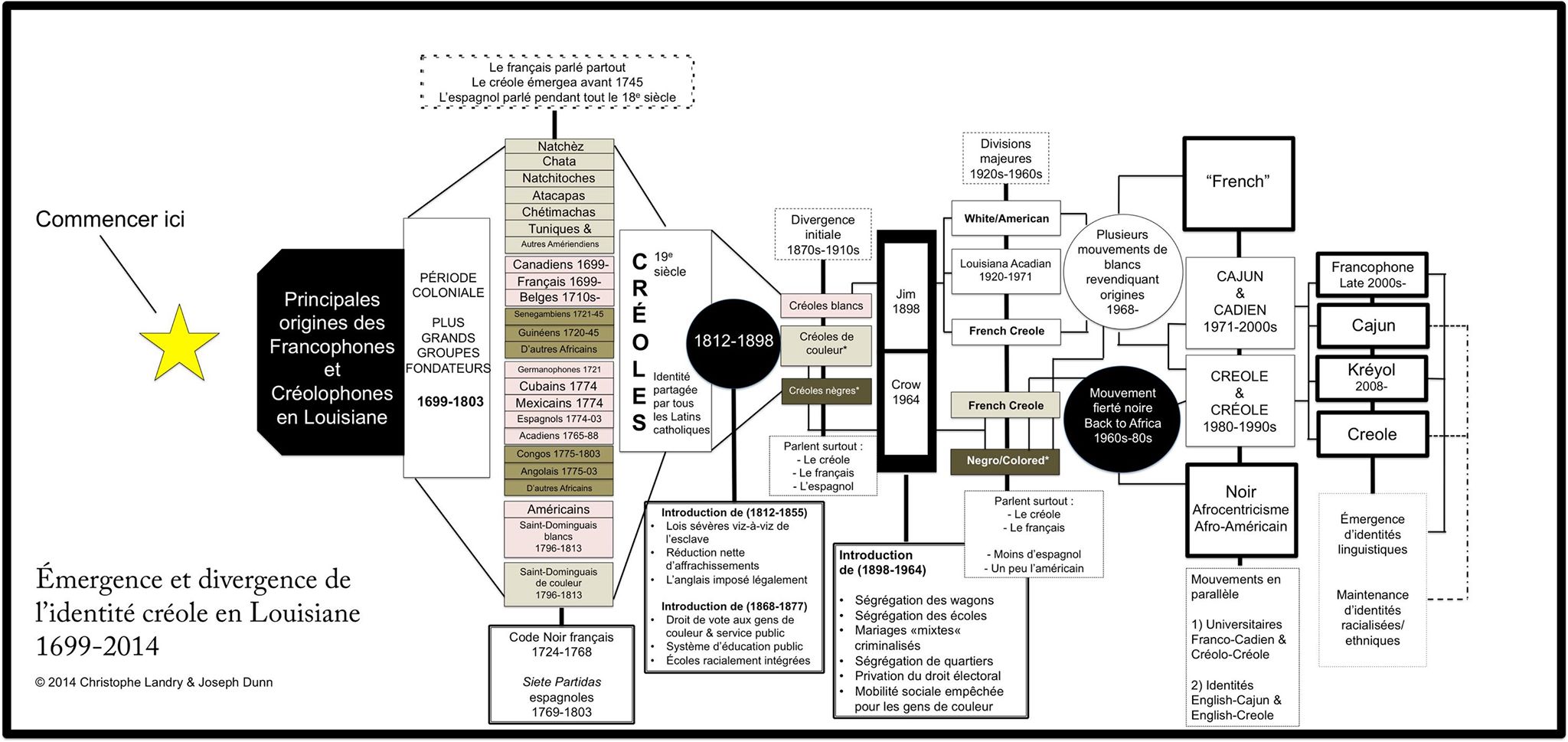

To understand the Creole world of the Duparc-Locoul family, it is important to imagine Louisiana at a time when English-speaking Americans were seen as immigrants and foreigners by the pre-existing Native American, European (mainly French and Spanish), and West-African (both enslaved and free) populations of the former colony, founded in 1699.

Following the transfer of Louisiana from France to the United States in 1803, a stalwart Creole identity emerged in Louisiana as a reaction to the flood of Americans pouring into the territory seeking land and economic opportunity. This new Louisiana Creole identity was anchored in native birth, the French, Créole and/or Spanish languages, and the Roman Catholic faith.

This inclusive identity transcended race, as it was claimed by people of white, black and mixed-race heritage. It also included the descendants of Acadian exiles (known today in English as, “Cajuns.”) This is evident in countless French-language historical documents, ecclesiastical records, francophone literature, and transactions involving enslaved people. The members of the Duparc-Locoul family are perfect examples of this créolité.

The French language was at the very center of Creole identity, so much so that Louisiana author and physician Alfred Mercier would write in French in 1883, “The day when we cease to speak French in Louisiana – which we can not at all believe – there will be no more Creoles.” This means that if someone no longer spoke French as his first language, he was quite simply “American.”

The 17-year occupation of New Orleans and the River Road plantation region by Federal troops during the Civil War and the Reconstruction period would bring about great changes. The Union Army was American and the language of administration was English. During the Jim Crow period of the late 19th century through the 1960s, Louisiana Creoles of all backgrounds would see themselves constantly pitted against each another as segregationist laws and policies were imposed upon them.

When public education became obligatory by state law in 1916, schools were segregated into white, black and Indian establishments. In 1921, a newly-adopted state constitution imposed English as the mandatory language of classroom instruction, relabeling French as a “foreign language.”

Louisiana’s French and Creole-speaking schoolchildren were thus not only separated and segregated from their linguistic and cultural peers, they were also forcibly assimilated into the English language and the American mainstream. Their relationship to their own heritage languages and culture would henceforth be defined by American English-speaking White Anglo-Saxon Protestant norms.

And so, the benchmark for identity in Louisiana shifted from language and culture to race and ethnicity as a direct result of heritage language loss, forced assimilation into English, and Americanization.

Today, we define Creole through culture, foodways, music, folklore, family traditions, architecture, the Catholic faith and genealogy. Even so, our attempts to understand the Creole world of our ancestors through an imposed English-speaking American lens often fall short of the complexities that characterized it.